Automatic language translation

Our website uses an automatic service to translate our content into different languages. These translations should be used as a guide only. See our Accessibility page for further information.

The following videos show how NCAT hears a range of disputes. They are intended as a guide to law and procedure only. You should get legal advice about the circumstances of your case.

This video shows how NCAT hears a tenancy application about unpaid rent. Also available in Arabic, Mandarin, Greek and Vietnamese.

Watch how NCAT hears a case where a landlord seeks orders to recover 8 weeks of unpaid rent from her tenant.

Watch how NCAT hears a case where a landlord seeks orders to recover 8 weeks of unpaid rent from her tenant.

Disputes between tenants and their landlords are common, and they often come before NCAT. They are handled by the Tribunal’s Consumer and Commercial Division and commonly relate to rental bond, repairs to the rental property, rent that hasn’t been paid, or ending the tenancy.

In the following scenario, Ling, a landlord, has taken her tenant to NCAT to try to get back 8 weeks of unpaid rent. The tenant is still living in the property, but Ling is experiencing financial hardship without the income that the rent provides.

Ling was the owner of a one-bedroom flat in inner Sydney that she rented out through a local real estate agent.

Her tenant, Joshua, was eight weeks behind in rent and refused to answer calls, emails and letters from the real estate agent. Ling tried to visit the property twice but Joshua was not home. So Ling sent Joshua a Termination Notice to end their rental agreement.

Ling then made an online application to NCAT to have Joshua evicted from the property for not paying his rent. She could have posted the application or given it in at the Tribunal in person, but she chose to complete her application online because it saved her time.

When NCAT received Ling’s application, her case was listed for ‘conciliation’ and a ‘group list’ hearing. Conciliation is a process where the parties try to settle the dispute themselves in an informal way. It can avoid the need to go to a full hearing. A group list hearing is where a number of different cases are dealt with during the same session.

The Tribunal mailed Joshua a Notice of Hearing to tell him about the pending action against him. The notice was sent with a copy of the application form and a copy of his rental agreement, which Ling had provided as an attachment to her application.

Ling was also sent a Notice of Hearing. Both Ling and Joshua’s notices suggested that they gather together all the evidence they could to support their cases. In a tenancy dispute, this evidence might include rent receipts or other rent records, a report describing the condition of the property when the tenant first rented it and any reports that have been made since they moved in, a copy of the termination notice, copies of all letters and emails between the landlord (or agent) and the tenant, photographs, receipts for work done at the property while the tenant has been there, and witness statements or statutory declarations from other people who might have something relevant to say about the case.

Joshua and Ling were told to bring all their evidence to the hearing in case they needed to refer to anything. They were also told that they did not need to bring witnesses. If they could organise their documents in a single folder it would make it easier to find things during the hearing.

Joshua and Ling were asked to arrive at the Tribunal at least 15 minutes before the ‘Conciliation and Hearing’ started to make sure they were ready when it began.

Ling and Joshua were shown to the Hearing room where their hearing was listed with a number of other cases in a ‘Group list’. For this reason, there were other people sitting in the hearing room who had nothing to do with their case.

Tribunal members are addressed by their surname; so the Tribunal Member asked parties to address her as ‘Ms Kim’.

Watch this video to learn about the role of NCAT's Guardianship Division.

Watch this video to learn about the role of the Guardianship Division of the NSW Civil and Administrative Tribunal.

Watch this video to learn about the role of the Guardianship Division of the NSW Civil and Administrative Tribunal.

Part 1: Introduction to the Guardianship Division

In hearings before the Guardianship Division, we try to be less formal than in other forms of legal proceedings, but nonetheless they're important proceedings.

The majority of hearings are heard by a three-member panel chaired by a lawyer. There's also a professional member. They are somebody who has experience in the treatment and assessment of people with decision-making disabilities. The third member is a community member, and they are somebody who usually has the lived experience of disability.

At the start of a Guardianship Division hearing, all participants will be asked to introduce themselves and explain their role in the proceedings.

The Tribunal will usually then give a brief overview of the legal test that's applicable to the hearing on that day.

The Tribunal will also go through the documents that it has received and make sure that the parties have received the same documents so that everyone has seen the same evidence.

The Tribunal then generally turns first to the applicant as the driver of the proceedings and asks them to outline why they believe the orders are necessary.

Each of the parties then will be asked to express their views on that as well, and importance of course, the subject person who hopefully is a participant in the hearing.

In most matters before the Guardianship Division, after a short break, the Tribunal will come back to the hearing room and announce their decision.

The issues which can delay proceedings is a failure to involve the subject person or to assist them to participate in the proceedings if they are able to do so.

Any failure to assist the Tribunal identifying the parties to the proceedings, as they are required to have notice of those proceedings, and any lack of evidence or any difficulty with the quality of evidence or a difficulty in ensuring that the author of any documentary evidence can participate in the hearing. All of those factors can possibly delay a matter getting a hearing or could cause an adjournment of a hearing.

Part 2: When can the Tribunal make a guardianship order?

The Tribunal can only make a guardianship order if it's satisfied of the legislative test provided in the Guardianship Act.

The first thing that we need to be satisfied of is "does the person have disability that impacts upon their decision-making".

Without clear evidence before the Tribunal on that important issue, we can't proceed to make any orders, even if we think that an order might be in that person's best interest.

So that's why it's so important, particularly if you're an applicant, that you provide us with clear documentary evidence as to the person's disability and how it impacts upon their ability to make decisions.

Part 3: What is the next step in the hearing?

Once the Tribunal is satisfied in a hearing that it can conclude that the person is someone for whom they could make a guardianship order, they need to decide whether to exercise the discretion to do so.

Before the Tribunal can do that, it needs to take account of the views of the person. That's very important.

If they have a spouse or a carer, they need to take account of their views. And then the Tribunal needs to decide why is there a need now, and that's particularly important if a person has had a lifelong disability or a disability for a long time. The question that really needs to be asked is "why now?".

Part 4: What information does the Tribunal need to make a guardianship order?

If the Tribunal receives evidence written from a treating health professional, it's not enough to simply say a person has dementia and therefore they need a guardianship order.

What we need is a much more fulsome report. A report that explains how long the person has been treating the patient, their history, what testing has been engaged in to assess their cognitive capacity, what's the formal diagnosis, how that diagnosis impacts upon their decision-making, and anything else that really will assist the Tribunal in making its decision.

It's especially important where there's conflict as to a diagnosis, or where there might be views in a hearing expressed that the person doesn't have a disability at all for example, that the person who writes the report is available to give evidence to the Tribunal. This would be best in person when possible, but certainly availability by phone is important in those matters.

Part 5: Why does the Tribunal insist that the subject person attend the hearing?

Often people enquire why is it necessary for the person, the subject of the application, to be involved in the hearing.

It's very important because, firstly the legislation requires us to take on board the views of the person wherever possible. And secondly, if we make an order for a person, it effectively can remove the most basic of rights to decide for yourself where you live and who you live with and what medical treatment you have.

So naturally we really want to hear from the person wherever possible. Obviously if a person is too unwell to participate, then that's a reason why they may not participate, but we need clear evidence of the illness.

Similarly, if it's asserted that because of their disability they can't express a view in the hearing, we need evidence that confirms that. And that's important also because if the person isn't able to come to the hearing, and the evidence before the Tribunal suggest that they could participate, that raises the likelihood of an adjoining.

There's also what's called the "coercive accommodation function". That's a very powerful order that allows a guardian to utilise the services of police, ambulance officers and others as necessary to take the person for whom they appointed guardian to a location and if necessary, keep them there for their own safety and wellbeing.

Part 6: When can the Tribunal make a guardianship order?

In order to make a financial management order, the Tribunal needs evidence around the person's inability to manage their affairs.

So evidence is needed from a treating health professional as to why they believe their capacity to manage their financial affairs is impaired in some way.

We need information as to the nature of their estate. So by that I mean their assets, their liabilities, their income, their debts and, of great importance, why is there a need for an order now.

Even if a person has appointed an enduring power of attorney, the Tribunal can proceed to make a financial management order if the evidence supports such.

Having said that, obviously given that the subject person has gone to the time and the trouble to make these appointments, there needs to be clear reliable evidence before the Tribunal as to why it should disturb those appointments.

If, however we are satisfied, we can proceed to make a financial management order that suspends for the life of the order, any power of attorney that's been appointed.

Part 7: Summary

The main points to remember if you're an applicant in proceedings is first of all, you're the driver of the proceedings. You’re the reason that the matter is occurring, and you need to ensure that wherever possible you have identified the parties to the proceedings, because the Tribunal is required to provide a notice of a hearing to the parties.

It's also important that you’ve provided us with the evidence necessary to support your application.

In terms of final advice for applicants, I think the best thing I can say is – the better the quality of the application and the evidence supporting the application at the get go, the less likelihood there is of delays of a matter receiving a hearing or having a final outcome.

Watch this video about a typical guardianship and financial management application to NCAT's Guardianship Division about a person with a decision-making disability. Also available in Arabic, Mandarin, Greek and Vietnamese.

Watch how NCAT hears an application by a family member to be appointed as a guardian and financial manager.

Watch how NCAT hears an application by a family member to be appointed as a guardian and financial manager.

Because they are getting older or have a disability that affects their decision making, some people are unable to make their own decisions about their care. Some people are no longer able to look after their own finances either.

NCAT’s Guardianship Division handles these cases. It decides on applications for appointing guardians and financial managers for people living with a decision-making disability.

Almost half of the applications in the Guardianship division are about people with dementia and more than 60% concern people over the age of 65.

In the following scenario, Steffi wants to apply for guardianship of her sister, Lena, who has dementia. She also wants to be appointed as her sister’s financial manager to allow her to look after Lena’s financial and legal affairs.

Lena is a 68-year-old woman who lives alone in a unit. Lena has a sister, Steffi, who has become more and more concerned about Lena’s wellbeing and worries that she can no longer look after herself physically or mentally, and that she is not able to take care of money matters anymore.

Steffi has also tried in the past to get Lena’s permission to take over her legal and financial decisions, but Lena has said no. She says she has done it for 50 years on her own and that she is OK to keep doing it herself. Steffi did not agree, but there was only so much she could do while her sister seemed to be getting by.

For a while, Steffi has thought that Lena has dementia but, because Lena keeps refusing to be checked by a doctor, no diagnosis of dementia has been made.

Steffi knew Lena needed fulltime care, but Steffi could not do anything without legal permission to make decisions for her sister.

A few weeks ago Lena had a fall in her home and ended up in hospital. The doctor said Lena was not looking after herself and she wasn’t eating properly. Lena spent some time in hospital and then moved to respite to recover.

The fall was a turning point for Steffi – she needed to get legal permission to take over her sister’s affairs.

As a first step, Steffi contacted the Tribunal about her options. NCAT explained that Steffi needed to apply for ‘guardianship’ of her sister. NCAT said that if her application was successful and she was appointed as Lena’s guardian, Steffi would have the right to make lifestyle and personal decisions on Lena’s behalf. Lifestyle or personal decisions include decisions about Lena’s medical or dental treatment, where she lives and what services she needs.

The representative from the Tribunal explained that to make a guardianship order, the Tribunal must be sure that Lena has a decision-making disability, that the disability means she cannot look after herself properly, and there is a need for Lena to have a guardian appointed.

The Tribunal representative also explained that to make a financial management order the Tribunal must be sure that Lena is not capable of managing her own money, there is a need for someone else to manage her money, and it is in Lena’s best interests that an order is made.

As part of the application process for guardianship and financial management of Lena’s affairs, Steffi had to make a formal application to the Tribunal. This meant she had to fill out an application form and provide medical reports about Lena’s physical and mental health and about Lena’s ability to make decisions.

When the Tribunal received the application, they had to first assess the risks to Lena, asking: What could happen to Lena if a guardian was not appointed for her? Is Lena in any immediate danger?

The hearing was held at an NCAT hearing location close to the facility where Lena was staying so that she could come to the hearing.

At the hearing Steffi brought along her husband and her sister Lena. Steffi told the three Tribunal members that Lena was diagnosed with depression in her 50s and since that time Lena hardly ever let Steffi visit her and rarely talked to her when she tried to telephone. Steffi said that about 12 months ago Lena started to have trouble remembering to eat or to take her medication. Steffi had organised Meals on Wheels and a care worker to visit Lena at her home but Lena had not let them into her unit.

Walter, a social worker, and Isaiah, a doctor specialising in working with older people who have mental health issues, both told the hearing that in their professional opinions, Lena has dementia. Sonia, a community mental health case worker, said that she had been working with Lena for the past five years and had noticed that Lena could no longer look after herself and her home. Sonia said that she noticed this the most in the past year and that Lena needed to be reminded to take her medication, make meals and to have showers. Sonia said that Lena now refused to see her and would not see her local doctor either.

The Tribunal asked Lena whether she thought she needed someone to help her make decisions about where she should live and other parts of her life. Lena told the Tribunal she wanted to go home and that she didn’t need any help. Lena was unable to say what she would do once she got home. When the Tribunal asked if Lena would like her sister to help her, Lena said ‘definitely not’. Steffi said that Lena would not accept help from any family member.

Regarding Steffi’s application for financial management of Lena’s money, Lena clearly told the Tribunal that she did not want a financial manager and that she would be fine to manage her money on her own. Lena told the Tribunal about her savings account and budget. She also said she wanted to buy a new unit closer to the beach. However, when the member asked for more information about her plans Lena was unable to explain how she would go about finding a new unit, how she would know she was getting value for money or what was involved in selling her existing home. Lena was also unable to tell the Tribunal what kind of people she should speak to about these plans and didn’t seem to understand that it would be hard to sell her unit and buy another one by herself because of her health problems.

In making its decision about the guardianship order, the Tribunal had to consider the risk to Lena against her right to make her own decisions. Before the Tribunal can appoint a private guardian, it has to be satisfied that the guardian and the person will be able to get along with each other and that there is no conflict of interest. The guardian must be willing and able to take on the role. The Tribunal can appoint the Public Guardian to make decisions for a person with a disability if there are no family or friends available or if it wouldn’t be right to appoint a private guardian for other reasons.

Because of her disabilities, the Tribunal decided that Lena had difficulty with making decisions and managing on her own. The Tribunal decided that there was a need for a guardian to be appointed because Lena would not let Steffi help her and decisions needed to be made for Lena that would probably be against her wishes but necessary to keep her safe and as healthy as possible. The Tribunal took into consideration that Steffi did not want to be Lena’s guardian because she was worried about the effect it may have on her relationship with her sister, especially if she had to make decisions that Lena did not agree with. Because there was no other suitable person available, the Tribunal appointed the Public Guardian to make decisions about Lena’s accommodation and her medical, dental and other healthcare needs for 12 months.

The Tribunal let Lena know that she could appeal the decision. Lena said that she would think about this but that she was happy that someone other than her sister would be looking out for her wellbeing.

Then it was time for the Tribunal to decide about Lena’s financial affairs. To make the right decision, the Tribunal needed to be satisfied that Lena was not able to look after her own money matters, that there were things that needed to be done about her money and property and that it would be better for Lena if someone else did these things. The Tribunal also had to decide whether Steffi would be the best person for the task. If Steffi was appointed, then she would be overseen by the NSW Trustee and Guardian. The Tribunal also had the option to appoint the NSW Trustee and Guardian to look after Lena’s money and property for her.

The Tribunal decided that Lena’s health condition meant she was incapable of managing her financial affairs because she was not able to plan for the future or make decisions about her pension and these things needed to be take care of. The Tribunal also decided that it was in Lena’s best interests for a financial management order to be made to make sure her money was looked after.

At the hearing, Lena told the Tribunal that she would prefer to have her sister manage her money rather than the NSW Trustee and Guardian. So the Tribunal made a financial management order for Lena, appointing Steffi to manage her sister’s affairs.

Most people with a decision-making disability manage with help from family, friends and service providers. They do not need a guardian or a financial manager.

But if you believe that a family member or someone else you care for needs someone to make lifestyle and personal decisions because they have a decision-making disability or needs someone to take over management of their financial matters, you can go online to www.ncat.nsw.gov.au to find more information.

This video shows how NCAT hears applications by home owners, traders and insurers about home building work. Also available in Arabic, Mandarin, Greek and Vietnamese.

Watch how NCAT hears a claim from a home owner seeking orders about incomplete work under a home building contract.

Watch how NCAT hears a claim from a home owner seeking orders about incomplete work under a home building contract.

NCAT’s Consumer and Commercial Division hears applications made by home owners, traders and insurers about home building work where the amount claimed is less than $500,000.

‘Home building’ means any residential building work done by a building contractor or tradesperson, such as when someone builds a new home, builds an extension to an existing home, puts in a swimming pool, or renovates a bathroom or kitchen.

In the following scenario, Winston has brought a claim against a developer who, he says, has not finished the work they agreed to in their contract.

18 months ago Winston bought a new duplex property off the plan from a developer.

While it was being built, Winston noticed a number of problems and things that weren’t being finished properly. Most of these problems were about extra things they had agreed to in the contract, such as an extra sink in the bathroom and a covered-in area in the backyard. The developer told Winston that everything would be fixed according to their contract before he had to make his final payment.

When the date of Winston’s final settlement came around, some things were still not fixed. Winston asked both the developer and the builder to come back to the property to finish the job. He asked more than once, but each time they refused.

Winston first contacted NSW Fair Trading. NCAT cannot take an application about a home building matter unless it has first been seen by Fair Trading.

A Fair Trading inspector visited the property and wrote a report describing the issues with the building and the things that were not finished properly.

Even after the Fair Trading report, both the developer and the builder still said they would not repair the property. After a few months of nothing happening, Winston applied to NCAT for help to get his home finished.

In his application to NCAT, Winston asked that the developer pay for the cost of finishing the work that was described in the contract and to also provide the things that he had ordered and paid for but not received. These included the extra sink and the covered-in space at the back. As part of his application, Winston gave NCAT the building report written by the Fair Trading inspector.

NCAT scheduled a ‘directions hearing’, which Winston was required to attend. The purpose of a directions hearing is to say what the dispute is about and to tell the parties what information they must provide to each other and the Tribunal. This material could include witness statements, experts’ reports, photographs and other documents with information about what happened.

NCAT then provides ‘orders’, which say in writing what each of the parties must do to get ready for the hearing.

The orders can sometimes be complicated but usually provide a short statement of what documents are needed.

In a building dispute, these documents can include what is called a Scott Schedule. Because Winston said that the work was not completed or was not completed properly, he needed to fill in a Scott Schedule. In the schedule he had to write down each problem and say how much it would cost to fix or complete. The developer then had to provide a response to Winston’s claim.

Sometimes, if both sides have an expert, the Tribunal will also make orders for the experts to meet and prepare a joint report describing the issues they agree and don’t agree on.

Later, NCAT scheduled a ‘Formal hearing’ where Winston’s case was heard by one Tribunal member. At the hearing, Winston was asked to tell his side of the story and was then cross-examined by the developer’s lawyer. Cross-examination is when the opposing party is allowed to ask the applicant questions directly in front of the Tribunal.

The developer said that Winston sometimes didn’t let them on the property, which meant they could not carry out work. Winston said this wasn’t true.

Winston’s witness, who was the building consultant who wrote the report, then spoke. He told the Tribunal what items on the builder’s list had been completed and what was still left to do. The building consultant was then cross-examined by the developer’s lawyer.

The developer’s witnesses then gave their evidence and Winston cross-examined those people.

At the end of the hearing the Tribunal member accepted Winston’s evidence and said that the developer did not provide enough evidence to disprove Winston’s claim.

The Tribunal ordered that the developer fix the problems and complete the other work. The member set a time for when this work had to be completed.

Both parties were told that if the developer did not do what the Tribunal instructed, then Winston would be able to renew the application and ask for money to be paid instead. The amount of money would equal the cost of getting the building work finished by someone else.

NCAT can hear all cases related to residential building work where the amount claimed is less than $500,000, but remember that you first must refer your case to NSW Fair Trading. You can call them on 13 32 20 for more information.

You can then make an application to NCAT online or fill out a home building application form.

Visit the website at www.ncat.nsw.gov.au for more information.

This video shows how NCAT reviews an administrative decision about licensing. Also available in Arabic, Mandarin, Greek and Vietnamese.

Watch how NCAT reviews administrative decisions when someone seeks a review of a NSW Government agency decision.

Watch how NCAT reviews administrative decisions when someone seeks a review of a NSW Government agency decision.

Some people turn to NCAT because they believe a New South Wales government agency has made a decision that affects them that is wrong.

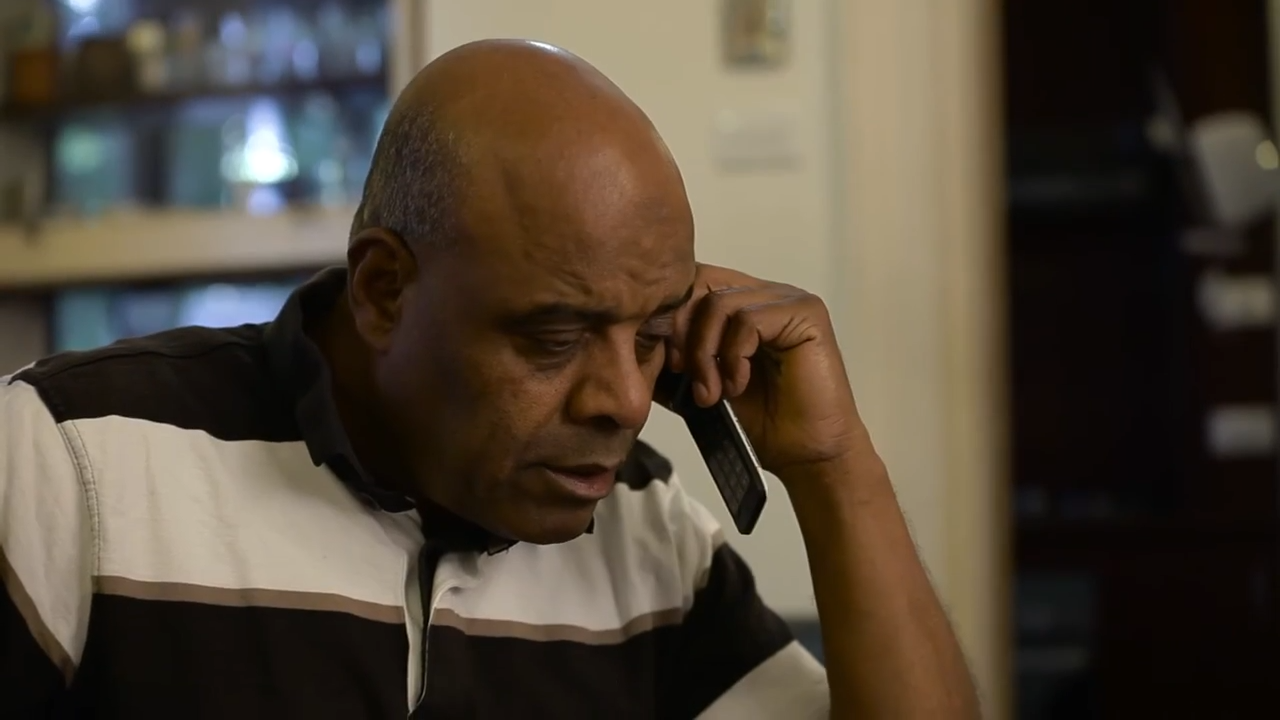

In the scenario that follows, Fadi, a taxi driver, believes that Roads and Maritime Services unfairly cancelled his authority to drive a taxi after some passengers complained that they had been charged too much for their taxi trip.

Here is how the case unfolded.

Fadi had been driving taxis in Sydney for five years.

A few months ago, Roads and Maritime Services told Fadi that he could no longer drive a taxi because passengers had complained that they had been overcharged. When they asked Fadi about these incidents, he said that he had not been driving his taxi on those dates so it could not have been him.

Nonetheless, Roads and Maritime Services said that because of the evidence given to them by the passengers, they were cancelling his authority to drive a taxi. Fadi was told this in a letter. The letter said that if he was unhappy with the decision he could apply to NCAT within 28 days for a review of the decision.

The letter also said that the decision would take effect immediately and if Fadi wanted to keep driving a taxi, he would have to apply for a ‘stay’ of the decision. A stay means that the decision is put on hold until the Tribunal makes its final decision. This requires a separate application.

Naturally, Fadi was very unhappy with this decision. Driving a taxi was the way he made a living, and without it, he would not be able to provide for his family. He felt that RMS’s decision was wrong and that he would find it hard to get another job because his English was not very good.

Knowing that he would have to speak about his case in front of the Tribunal, Fadi had to decide if he wanted a lawyer or agent to help him. Fadi didn’t feel he had enough money to pay for a lawyer so chose to phone LawAccess for free legal advice instead.

To have his case heard at NCAT, Fadi had to fill in an application form from the Tribunal’s website. Following the website’s instructions, he then had to make two copies of the application and the letter from RMS.

Fadi posted the application with a cheque for the filing fee to the NCAT Registry. He also filled out an application for a stay so he could keep driving his taxi until a final decision was made about his case. Fadi was not able to drive his taxi while he waited to hear back from the Tribunal about the stay.

Fadi soon received a letter telling him that a date for his ‘stay hearing’ had been set. The Tribunal’s letter also said two other things. First, it told him that NCAT had sent his application to RMS. Second, it asked if Fadi would need any extra help with the hearing because of a physical disability or problems with English, for example. The letter said that Fadi should let the Tribunal know if he needed this kind of help.

In the meantime, the Tribunal ordered RMS to provide all of its documents that related to Fadi’s case and to explain why they made the decision to cancel his taxi licence.

Fadi wrote a statement that said the reasons why he should be allowed to continue to drive until the Tribunal made a decision. He sent the statement to the Tribunal and to RMS.

At the stay hearing, the Tribunal Member listened to Fadi and to a lawyer from RMS. The Tribunal Member considered all the relevant information including the problems it would cause for Fadi if a stay was not given and whether it was in the public interest for him to continue to drive. The Tribunal Member decided that Fadi could continue to drive until a final decision was made.

The Tribunal also made the following orders.

RMS had to send to NCAT and give to Fadi any of the section 58 documents that were not yet provided.

Fadi had to send to NCAT and give to RMS any relevant documents that he had not already provided. These documents could include character references or statements from people who could say where Fadi was at the times when passengers said they had been overcharged.

RMS had to provide any documents in reply to Fadi’s documents by a certain date.

The Tribunal Member also told Fadi the date of his hearing and that it would probably take half a day. The Member said that the location of the hearing could be a regional area if that was the most convenient for the parties and witnesses.

When he received copies of the documents provided by RMS, Fadi made sure he read over them very carefully so he could properly understand the case that RMS would put forward at the hearing.

Fadi knew from the letter and what the Member told him at the stay hearing that the legal test that the Tribunal would use in his case was whether he was a ‘fit and proper person’ to have a taxi licence. The Tribunal Member had also told him to think about what evidence he could provide to help his case. This could include witness statements, character references or medical reports if they were relevant to his fitness to drive a taxi. Fadi knew that he could only use the documents that were provided to the Tribunal and given to RMS before the hearing. Fadi understood that he had to provide these documents by the date given at the stay hearing.

When the day of the hearing arrived, Fadi was very nervous. He didn’t want to lose his right to drive a taxi and was worried about his ability to argue his case well enough to convince the Tribunal to overturn RMS’s decision.

When he arrived at the Tribunal fifteen minutes before his hearing, the first thing Fadi did was to check the list to see what hearing room his case would be heard in.

When Fadi arrived at the hearing room, the Member of the Tribunal who would hear the case introduced herself. The Member asked Fadi to sit at the long table opposite her, next to the person from RMS. There were three people sitting at the back of the room – one was a passenger who said Fadi had overcharged him.

The Member explained that the hearing would be sound recorded. She asked Fadi to call her ‘Ms Bradbury’ and to call the lawyer from RMS ‘Mr Oliver’.

The lawyer from RMS explained that RMS had cancelled Fadi’s taxi’s licence because he had overcharged passengers.

RMS then asked one of Fadi’s passengers to answer questions in front of Ms Bradbury. The passenger confirmed that Fadi was the driver who overcharged him.

The Tribunal Member then asked Fadi if he would like to ask the passenger any questions. This is called ‘cross-examining’ a witness. Cross-examination means asking the witness questions about their statement.

After a short break, it was time for Fadi to tell his side of the story. He didn’t have any witnesses but had already handed in a statement from his wife saying that Fadi had been home with her on the days the passengers said they were overcharged. The lawyer from RMS was then able to cross-examine Fadi with questions, which Fadi answered.

Once all the evidence had been presented, both Fadi and the lawyer from RMS were given the chance to make submissions. Submissions are arguments about the meaning of the legal test, which, in this case was what ‘fit and proper person’ means, and whether the evidence showed that Fadi was in fact a fit and proper person or not.

RMS argued that Fadi was not a fit and proper person to hold a taxi licence because he had deliberately overcharged passengers for his own personal gain and then lied about it.

Fadi said that he had done nothing wrong and that because he did not do what RMS said he did, he should be considered a fit and proper person to drive a taxi.

Sometimes the Tribunal Member will make a decision about the case at the end of the hearing and give the reasons at that time. In Fadi’s case, the Member said she would need to think about all the evidence and then write down her decision. In the meantime, Fadi could keep driving his taxi because a stay had previously been made.

The Member explained that the decision would be either that RMS made the correct decision in cancelling Fadi’s taxi licence, or that RMS did not make the correct decision and Fadi’s licence would be given back.

Lastly, the Member explained that the Tribunal’s Registry would contact both parties by phone the day before the decision was due to be published on the internet. She said that no-one would need to come to the Tribunal because a copy would be posted to both parties and then published on the NSW Caselaw website.

Do you feel like a wrong decision has been made against you by a New South Wales government agency? You can find out more by visiting the NCAT website at www.ncat.nsw.gov.au.

Last updated: